Imani[1] is a mother of three living in Mississippi. Faced with an unplanned pregnancy and financial difficulties, Imani knew when she was six weeks pregnant that she wanted an abortion. But the costs added up quickly.

Her first doctor’s appointment cost $150, which insurance did not cover. As a single mom without a car, the visit also required her to pay for a cab ride and find childcare. Already strapped for funds, Imani wasn’t able to secure

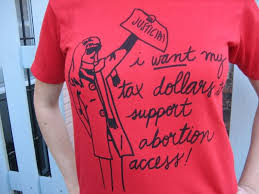

Image: Repeal Hyde Art Project

enough cash for the visit until she was 17 weeks pregnant. Relieved to finally have made it to the appointment, Imani’s heart stopped when she was told at 17 weeks that she was one week too late to receive abortion care in Mississippi. Imani is not alone.

T h e N u m b e r s

According to the Kaiser Family Foundation, 13.5 million women of childbearing age on Medicaid can be denied coverage for an abortion.

Millions of women face an unplanned pregnancy each year, and many can’t access the safe, comprehensive reproductive health care they need. This includes basic pre- and postnatal care, access to birth control, emergency contraception, and abortion care.

Roe v. Wade may have changed the law in 1973 by recognizing a woman’s right to an abortion, but anti-abortion politicians in 1977 managed to find a way to withhold abortion from those who had the least amount of political and economic power. The provision known as the Hyde Amendment prohibits federal funds from being used for abortion care.

So how does Hyde affect the 13.5 million women of childbearing age on Medicaid? Despite being on financial assistance, women must pay out of pocket for an abortion. Many low-income women are also women of color, immigrant women, incarcerated women, and young women. By re-passing Hyde every year, politicians condone segregating reproductive health services, despite the fact that these are services many women will need to consider during their lives.

Studies have shown that access to abortion care is integral to taking care of ourselves, being financially independent, pursuing education and careers, and taking care of the families we already have. Because of the restrictions from the Hyde Amendment, women have to clear near impossible hurdles.

O u r E x p e r i e n c e s

Imani is one of us. As activists, we come to the issue from different places and with different identities. As a Congolese immigrant woman in Philadelphia, and as a disabled low-income black mother in Mississippi, we understand the barriers economically disadvantaged women and families face in accessing health care services. Between possible language barriers, cultural differences, unfamiliarity and distrust of the American health care system, the struggles faced from living in rural southern communities, or even blatantly anti-choice faith communities, the obstacles are steep. We have lived these first-hand.

Luckily, the Mississippi Reproductive Freedom Fund (a three-person, volunteer-driven organization) was able to help Imani. Local grassroots abortion funds are one of the only safety nets out there for women facing this struggle, and they work tirelessly to provide the services and support individuals need to get an abortion.

As reproductive justice activists and fund members, we intimately know the barriers women face when trying to access abortion care. From Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, to Jackson, Mississippi, we have witnessed the same heartbreaking problem: there is no such thing as “choice” if you can’t afford your abortion. At the Women’s Medical Fund in Philadelphia, we assisted over 2,100 people last year. Of those, 60% had Pennsylvania Medicaid but were unable to use their insurance to pay for their abortion because of Hyde.

Unlike Pennsylvania and Mississippi, a small number of states allow Medicaid coverage of abortions, but even in these states, politicians have been proposing a record number of laws to greatly limit access. These laws are often passed under the guise of protecting women’s health, but actually do the opposite by blocking the path to safe services and forcing women to delay their procedure, therefore increasing the cost and risk. Popular laws have included imposing medically unnecessary procedures and practices like mandatory waiting periods, ultrasounds, and counseling sessions. These laws assume women don’t know what they want, or that women get abortions on a whim.

We know this isn’t true. By the time women call an abortion fund for assistance, they have already deliberated, hustled, and worked hard to find money for their procedure. This is not an frivolous or inexpensive decision.

Abortion funds work on the front lines, and with this we see that economic justice is inseparable from reproductive justice. One can never truly make the best decisions for their family if you can’t afford the options. For many, regular contraception access is not a reality, meaning that exercising reproductive self-determination remains out of reach.

One in four Medicaid beneficiaries are forced to carry a pregnancy to term because they are unable to afford their abortion. Studies show that women who are turned away from the abortions they seek because of a lack of funds are significantly more likely to fall further into poverty. Individuals and families who are already struggling are often politicians’ first target when withholding services and resources for quality education, healthcare, jobs, and safe neighborhoods.

Abortion funds are taking calls from those who have nowhere else to turn. Despite being nationally spread out, we are united under the National Network of Abortion Funds. Being part of a national collective force enables us to pool resources, share our work, learn from each other, and support each other. We’re able to use our local community roots and connections to provide care that resonates with the people around us, whether at the last abortion clinic in Mississippi, or in a bustling city like Philadelphia.

In addition to the daily work of raising money to help women in need today, our work requires us to be creative and proactive in ensuring abortion access for tomorrow. We do this by engaging in public education and advocacy work with local community partners, and through national campaigns such as All Above All. Our collective work amplifies the local work we do individually.

In addition to the daily work of raising money to help women in need today, our work requires us to be creative and proactive in ensuring abortion access for tomorrow. We do this by engaging in public education and advocacy work with local community partners, and through national campaigns such as All Above All. Our collective work amplifies the local work we do individually.

We stand in unity, lifting marginalized voices and acknowledging, as Audre Lorde does, that, “There is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives.” To this end, we believe in engaging a large-scale anti-Hyde movement, and in building bridges with non-traditional partners. The sociopolitical landscape won’t change unless we all stand up for each other. Women’s dreams matter, and we must do more to eliminate obstacles on our collective path towards comprehensive reproductive freedom.

[1] Name changed to protect identity.

Joséphine Kabambi is the Program Coordinator at the Women’s Medical Fund, an abortion access organization that works to protect the ability to access abortion care though financial support, public education, and advocacy work. WMF is a member fund of the National Network of Abortion Funds.

Laurie Bertram Roberts is a black queer reproductive justice activist, freelance writer and doula from Jackson, Mississippi. She is a co-founder and board president of the Mississippi Reproductive Freedom Fund and President of Mississippi National Organization for Women. When not fighting oppression and inequality, she is likely watching Doctor Who or engaging in geeky activities with her seven children.

Categories: Health

We Testify: Shattering Stigma With Abortion Storytelling

We Testify: Shattering Stigma With Abortion Storytelling  Meet The Company That Wants To Make Your Tampons Safe

Meet The Company That Wants To Make Your Tampons Safe  The State-Level Court Ruling on Birth Control You Should Pay Attention To

The State-Level Court Ruling on Birth Control You Should Pay Attention To  Stigma and Resilience: Supporting Young Parents and Two Sides to the ‘Choice’ Coin

Stigma and Resilience: Supporting Young Parents and Two Sides to the ‘Choice’ Coin

There are people who answer all this with “how about adoption” but (1) It’s not poor women’s jobs to have babies for other people and (2) We have no idea what an individual woman’s response will be to giving a baby up. In far too many cases (even one is too many) they grieve so hard that it interferes with their functioning which ALSO makes it very difficult to impossible to ever get out of poverty. And the effects on other siblings of seeing their baby brother or sister given to strangers are incalculable.